The mythologies I grew up with never looked so good. While some folks find screen adaptations of stories they heard or read almost never living up to their mental movies, I’m not in that camp. It’s often fun for me to watch actions and scenes leap from pages to screens – I have a pretty low-budget imagination so movies these days tend to look way better than what my inner Ed Wood can conjure. Not all the time, of course. But, in Nezha’s case, definitely.

Loosely based on a story from the epically-named classic literature Investiture of the Gods, the animated feature directed by Yang Yu (aka Jiaozi) puts fire in the belly of a famous character. Nezha, a boy deity whose brattiness is just as well-known as his enchanted ‘gadgetry’, is brought to life with spirited kinetics and emotional flourish.

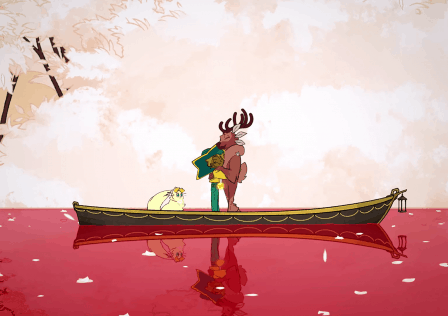

Carrying the imaginative vigour of Pixar and Dreamworks, the computer-generated (CG) visual fest remains rooted to its Chinese origins, both in its aesthetics and its soundtrack. Nezha’s gorgeously-rendered settings (such as the utopia/training ground hidden inside a painting) is a joy to watch. Its pupil-popping action – especially during the climactic showdown – does seem indulgent at times, but come on, it is a fantastical fight between celestial superheroes and the ruler of heavens.

Nezha’s strength, however, extends beyond rich visuals. What anchors the animated blockbuster is a heavy emotional core – which is refreshing for a production targeted at kids from this part of the world.

The movie begins with the Primeval Lord of Heaven, Yuanshi Tianzun, quelling a sentient Chaos Pearl by splitting it into a ‘heavenly pill’ and a ‘demon pill’. The Lord of Heaven then tasked the celestial being Taiyi Zhenren (Zhang Jiaming) to place the heavenly pill inside the womb of the pregnant Lady Yin (Lü Qi), who is the wife of Li Jing (Chen Hao) – both nobles of the demon-infested Chentang Pass. This would lead to the birth of their son, who is to be named Nezha.

However, in a drunken stupor, Taiyi Zhenren fell to the sabotage of his rival Shen Gongbao (Yang Wei) and caused the demon pill to be infused with Lady Yin’s baby instead. Hence, Nezha (Lü Yanting) is born a demon-child, and destined to be killed in three years by Tianzun’s irreversible curse.

In the meantime, Shen Gongbao has stolen the heavenly pearl and presents it to the dragon Ao Guang, Lord of the Eastern Sea, who used it to birth his own son – Ao Bing (Han Mo). With the powers of the pearl, the pretty boy with dragon horns shoulders the hope of his entire condemned tribe to escape their ‘prison’ in the ocean depths and ascend to higher office. Or maybe it’s heaven. In Chinese mythology, it’s sometimes hard to tell.

As Ao Bing trains diligently, Nezha’s death sentence draws near. But his more pressing ‘punishment’ are extreme boredom and a lonely existence. The boy is under permanent house arrest – a promise his parents made to the repulsed villagers of Chentang Pass when he was born so that they would spare the demon baby’s life.

But the restless Nezha frequently escapes into the village. Other kids despise him, so the impish protagonist amuses himself by pranking the villagers, which only fanned their hatred for him. Thus, Taiyi Zhenren took Nezha as his apprentice, training the end-of-the-world bringer to harness his demonic powers for good in his short remaining days.

Nezha himself began to believe that he can be a hero, and it is in one of his rescue missions that he encountered Ao Bing. The fiery kid and the water dragon boy become fast friends, unaware that the prophecy – and conniving celestial beings – are setting them on a path that fulfills a Chinese saying: ‘水火不相容’ (water and fire can never co-exist).

With a child’s impending death hovering over the story, it is a marvel that Nezha is still largely fun and entertaining. The movie’s biggest triumph could be its finesse in balancing big gags and bigger actions with small breathers. In these quiet reprieves, the emotions get to sink in, and sometimes turn on the waterworks.

My favourite of such moments has to be when Nezha and Ao Bing play jianzi (sort of like hacky sack) by the beach with moves that would have put a normal person in the hospital – in fact, Lady Yin had to protect herself with a full armour when playing with her son in an earlier scene. Nezha and Ao Bing are not only each other’s first friends, they are each other’s first equals.

Their similarity is not only in their super powers. Nezha and Ao Bing both have their futures laid out for them. The former is staring at a doomed fate while the latter is saddled with the expectations of his family. At its core, Nezha calls to young people charting their own path – a message that may seem stale to the Western world, but remains relevant in Asia, where arranged marriages still thrive and parental pressure still dictate lives.

Yet Nezha is not just a relatable movie for youths. It is also an important watch for the adults in their lives. Throughout the film, Nezha’s parents and teacher worked together incessantly to put the boy on a path of purpose, which is especially full of stumbling blocks when Nezha is born different. They did not give up, nor did they point fingers.

The same cohesion seems lacking among real-life teachers and parents. Among the teaching community, whether in Asia or the world at large, a common grumble is that parents are pushing the responsibility of disciplining their kids entirely to teachers. But among parenting circles, fingers are pointed at teachers for being incompetent and lacking in standards. While both sides may have their justifications, Nezha is a reminder for each to step up and work together, instead of turning on one another.

Beyond parents and teachers, perhaps Nezha is most pertinent for the biggest ‘nanny’ of China – the government. The film has a central – almost clichéd – message against prejudice based on one’s looks and origins, and it is difficult to watch it without thinking about the Chinese government’s ongoing persecution of Muslim minorities, which experts say are fueled by the state’s prevalent Islamophobia.

The question, of course, is if this anti-bigotry message matters to the Chinese audience who has propelled Nezha to be the second-highest grossing film in China – the top-grossing is still Wolf Warrior II, a film about a Chinese beefcake commando saving Chinese hostages from savage African rebels and amoral Caucasians.

Also published on Medium.

writes about pop culture with the suspicion that it is actually writing her.