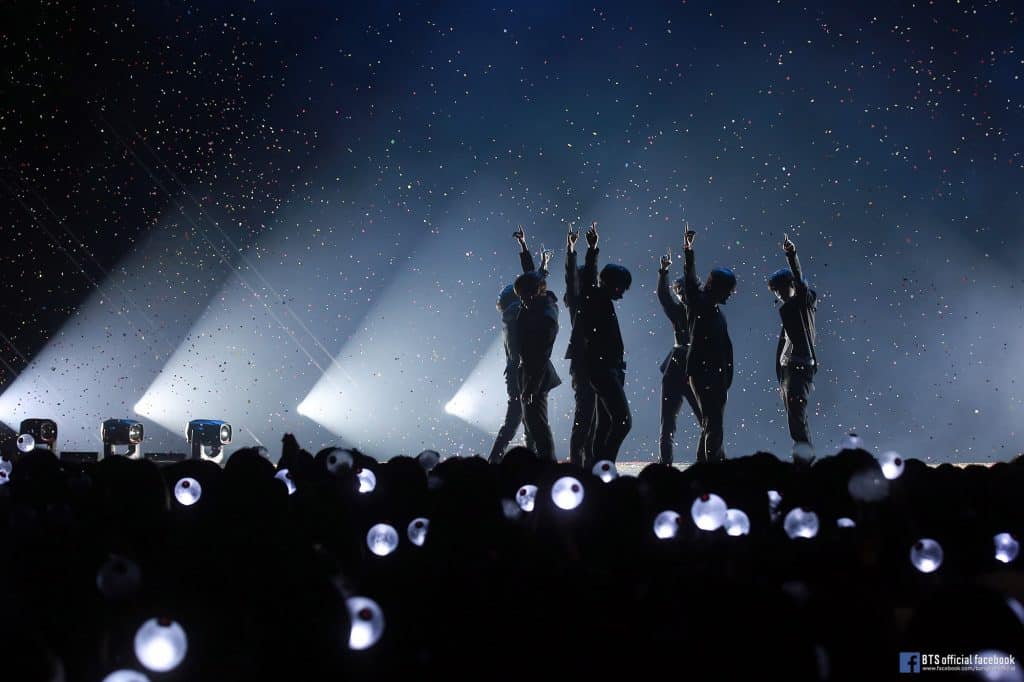

Cover picture | Source: BTS official Facebook page

Atiqah Sulaiman had a secret. While her friends knew her as an indie-rock chick, she hid a playlist. It was full of Korean pop (K-pop) songs that she listened to when no one was around. Already grappling with social anxiety, Atiqah was worried about being judged – K-pop lovers are widely stereotyped as shallow and obsessive fans fawning over pretty faces and, well, nothing much else.

After all, K-pop itself is often brushed off for being an idol industry peddling vanity, aegyo (flirty cuteness), and dazzling dance moves in schizophrenically-filmed music videos.

“You can say I was a closet fan. When I’m alone, I’d listen to K-pop. But when someone asks me to put on my music, I’d whip out another playlist with bands like Arctic Monkey or (Japanese rock act) Flumpool,” the 30-year-old social media strategist recalls.

Atiqah remembers the incredulous looks and patronising gazes whenever she comes clean about her music taste. But the embarrassment also stemmed from a latent guilt of liking something without a good reason. “Even I had to admit that some of the lyrics of K-pop songs I liked were pretty meaningless. It’s totally guilty pleasure.”

That was before she discovered BTS – one of the biggest deals in the K-pop kingdom now. Atiqah’s fate with the chart-topping, seven-oppa band was sealed during a particularly harrowing period at work. As her stress levels peaked and her mood plunged, she stumbled upon the BTS song ‘Tomorrow’ on Spotify.

“The song is basically about how we may seem trapped in a cycle of repetition every day, but we can believe that tomorrow will be better,” she recalls.

A simple message, but one that kept her from crumbling. “This was it. This song made me [a member of the] ARMY.”

The ARMY (which stands for Adorable Representative M.C for Youth) is the official fan club of BTS. Like Atiqah, many members have similar stories – that BTS songs helped them survive dark days.

After all, the band – made up of members nicknamed RM, Jin, Suga, Jimin, V, Jungkook and J-Hope – is forthcoming about their own struggles with pressures. Their lyrics, many of which were written by the band themselves, tackle topics like self-harm, academic stress, inferiority complexes, bullying, depression, and so on.

These real-world messages veer sharply away from the highly regimented K-pop industry engineered to sell perfection – a façade cracking under the slew of idol suicides and media exposés on draconian management.

Another fan, Shashfiny Chua, tells DeconRecon that she had always loved catchy pop songs, but as she grew older, these tunes begin to sound vapid and “are somehow all about romance and breakups”. BTS songs, on the other hand, are a breath of fresh air – they carry meaning that helps her deal with reality.

Atiqah Sulaiman (left) and Shashfiny Chua with their BTS merchandise

For Atiqah, BTS inspired confidence in her own life. Although she still gets socially anxious, she mustered the courage to fly to South Korea alone to attend a BTS concert and made friends with a stranger she met at the show.

Boys with Luv

BTS’ social angle is always cited by the ARMY as the top reason for their ardent support. They are, in many ways, empowered by meaning.

Atiqah, for example, is an open fan these days, but her pride is specific. “When people ask if I’m a fan of K-pop, I’d say no, I’m not a fan of K-pop. I’m a fan of BTS.”

Collectively, this pride culminates into fearsome protectiveness that powers the ARMY. The military connotation for a band that once went by its full name Bangtan Sonyeondan (Bulletproof Boy Scouts) seems fitting – the fandom is a formidable, at times zealous, defense unit. But this risks oversimplifying the global swarm of self-appointed ambassadors, evangelisers and “body armour” of BTS.

BTS debuted six years ago. But the band has already broken into the international stage at a scale surpassing many of their sunbae (‘senior’ in Korean).

Singing predominantly in Korean, BTS emerged last year as the first K-pop group to have topped the US album charts. In the same year, the Bangtan Boys also suited up to speak at the United Nations about “self-love”, presented an award at the Grammys, and sold out concert tickets for their tour in U.S. and Europe.

Seven months into 2019, the floppy-haired septet would go on to chart five No. 1 hits on Billboard’s World Digital Song Sales.

No matter what one feels about K-pop, BTS’ hard work and talent is undeniable. Their precise dance moves come from constant training. They produced many of their own songs. They update fans on their daily lives more consistently than many of us do for our own mothers.

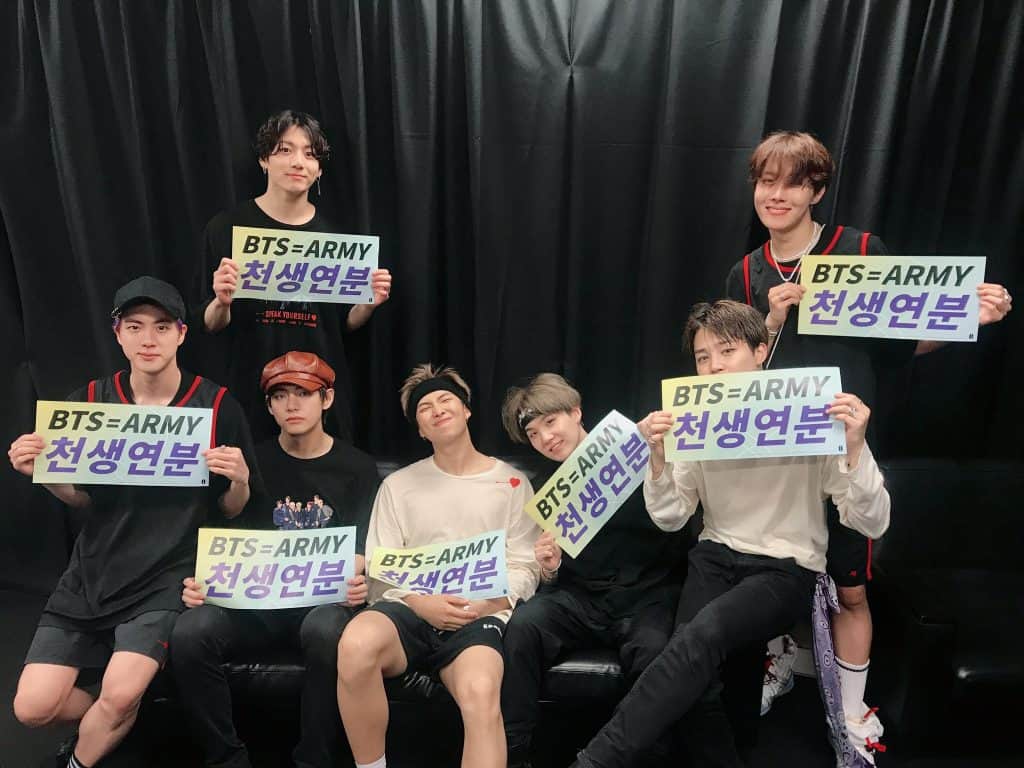

But it is hard to not mention their career highs in the same breath with the ARMY, especially when the idols credit their fans every chance they get – setting off an explosion of (purple) hearts across social media whenever they do.

The ARMY is a collective tour de force of clicks, views, purchases, and votes whenever the band drops anything new. A phenomena as big as BTS themselves, the ARMY is a strange amalgamation of loose organisation but precise coordination.

There is no set ‘criteria’ of being a member of the ARMY. If you identify yourself as one and act like one, you are one. Atiqah, for example, has been a card-carrying member of the BTS fan club since two years ago. Chua, on the other hand, just received her membership card two weeks ago. Yet both recognised themselves and each other as part of the ARMY long before Chua got her card, and make comparable investment of time and money on BTS activities and merchandise.

“[The ARMY’s] social media and OTT (over the top) activities cannot be explained by conventional organisational theories. There is no leader, everyone is (nominally) a leader, and everyone can partake in the action,” note associate professors WoongJo Chang and Shin-Eui Park, who are from Hongik University and Kyung Hee University in Seoul respectively, in their research paper on the BTS fandom.

“When BTS arrives at the airport for concerts in the U.S., some members of the local ARMY spontaneously form a kind of guardian group, keeping the throng of fans in line to make sure they do not generate any shameful spectacles or accidents.”

The lack of central command does not impair the ARMY’s military-like coordination. They learn and synchronise convoluted fan chants and illumination patterns using electronic light sticks during concerts. They mobilise fan projects from making banners to buying ad space on Times Square billboards in New York City.

Online, the ARMY exchange tips and coordinate mass ‘streaming parties’ to drive up BTS’ views and rankings on YouTube or Spotify. In April, BTS’ new single ‘Boy with Luv’ featuring American singer Halsey smashed YouTube’s record for the most-viewed debut in 24 hours, scoring 74.6 million views in that period (though the figure was surpassed recently by Bollywood rapper Badshah).

Chang and Park write: “… it is well known that ARMY has been operating a so-called ‘attack team’ to increase the number of radio submissions for the Billboard Music Awards (BBMA), and the ARMY’s dedication to boosting these indicators for those rankings.”

BTS ended up bagging the BBMA Best Social Artist – measured by fan votes and social media engagement numbers – for the third consecutive year in 2019. They also emerged as the first K-pop group to win the ‘Top Duo/Group’ category, beating Maroon 5, Imagine Dragons, Panic at the Disco, and Dan + Shay.

Going great lengths for BTS seems intrinsic to what makes one a member of the ARMY. This is partly why a 31-year-old Malaysian, who only wants to be known as Esther, finds herself in a peculiar navigation of identity.

Esther likes listening to BTS. She sees herself as a fan of the group, but thinks that she doesn’t “qualify” as one. She only buys a select few of BTS’ merchandise and albums, does not participate in the voting and streaming parties, and likes other bands – all no-nos among much of the ARMY. “There’s no official rule [of being a fan], but if other fans don’t ‘acknowledge’ me as a fan, am I still a fan?” she asks, laughing.

Denise, a friend of Esther’s joining in the interview, chimes in that some of her friends are hesitant to be called K-pop fans due to its “obsessive, fanatic” connotations. She acknowledges that not all fans behave that way, but there were some who went too far. For example, BTS’ management agency Big Hit Entertainment had blocked a list of overzealous fans (known as ‘sasaeng’) earlier this year.

Esther observes that the obsessive and possessive tendencies, including policing what their idols should or should not do, come from the hefty investment of time and money on the bands. “Their status has transcended from ‘fans’ to ‘investors’. The sentiment is that ‘I made you’.”

Pied Piper

BTS are not the only boys with luv. Aside from the ARMY, fandoms of other K-pop groups like TWICE, EXO and BlackPink are just as coordinated to ensure their favourite idols get seen.

Writing for Korea Exposé, researcher Katelyn Hemmeke pointed out that South Korea’s history of organised fandom began with a 1992-debut called Seo Taiji and Boys– a dance trio widely credited as the advent of K-pop. Their fan club is known as ‘Taiji Mania’.

“Taiji Mania is largely credited for creating a much more organised fandom, existing not just to chase after the stars, but to implement coordinated agendas for the sake of their artists. For over two decades, Taiji Mania has not only raised money and awareness for environmental causes (including the Brazilian rainforest), it has also worked to improve the music industry and reform South Korea’s copyright laws,” Hemmeke explained.

For BTS, the power of coordinated fandom has crescendoed to a global cultural phenomenon. Within a day of the band dropping its new album Map Of The Soul: Persona, it has topped iTunes album charts in 86 countries from the US, Europe and various parts of Asia.

According to the Hyundai Research Institute, BTS is worth more than US$3.6 billion to the South Korean economy every year – on par with the contribution of 26 mid-sized companies.

The scale and zeal of the Army give BTS the Midas touch that brands salivate for. Endorsement deals from Hyundai, Puma, LG Electronics, Coca-Cola, Line messaging app and more are rolling in.

Coca-Cola’s limited edition collection featuring BTS on its packaging

Other brands generously pepper their tweets with mentions of BTS and the ARMY in the hope for eyeballs through retweets or engagements. BTS is mentioned an average of 600,000 times on Twitter per day, reports Brand Watch.

And the ARMY happily oblige. When shampoo brand TRESemmé tweeted that BTS is “their new hair idols”, they scored 38,000 retweets – a sharp jump from the usual one to three retweets it got for previous posts. BTS is not an official endorser of TRESemmé – yet.

Toy brand Mattel saw a flood of 10,000 new Twitter followers within two days of its teaser featuring new BTS dolls, according to data firm Thinknum Media.’

“The wave crashed on March 25, when Mattel fully announced its line of official BTS dolls to the tune of 61,000 retweets, 137,000 likes, and over 31,000 replies,” writes James Mattone of ThinkNum Media.

But the effect wore off as quickly as it hit. Over the next two days, Mattone notes, Mattel’s Twitter account saw a drop of 4,000 followers and its “recent posts are barely in the teens of retweets and replies”.

When asked if she feels that the ARMY is being taken advantage by brands, Atiqah admits that she is conflicted. On one hand, more social media ‘mentions’ mean more exposure and fame for BTS. Some of these posts are also harmless – for example, the banter that TRESemmé shared with Pantene in a ‘battle’ over BTS were all in good fun, she opines.

On the other hand, Atiqah is unhappy with brands that pit BTS against other K-pop bands and, whether wittingly or unwittingly, incite ‘fan wars’. She believes that competitions like these provoke fans unnecessarily to harvest social media engagement numbers.

One example was the poll by FIFA World Cup last year on the song to play at its stadium during the 2018 Russia World Cup. Among the choices are BTS’ “Fake Love” and EXO’s “Power”. Devotees of both bands engaged in an online rivalry that turned bitter, to the point that some fans are calling for their own sides to calm down.

“Sometimes I do feel ‘exploited’,” she says. “But at the end of the day, the ARMY still holds the power.”

Fake Love?

With great power comes great responsibility. The same phrase motivating Spider-Man’s heroism is now applicable to the BTS Army, who seems bent on saving the world – one social initiative at a time.

Thanks to fans from around the world & the #BTSARMY, we reached our maximum donation goal of $1M. Funds unlocked through this campaign will help @UNICEF provide food packets to children suffering from malnutrition. Happy #StarWarsDay! Learn more at https://t.co/YWzgNoK6es. pic.twitter.com/gpvsFANzJv

— Star Wars (@starwars) May 5, 2018

Last year, the ARMY was specifically mentioned by Star Wars’ official Twitter for helping the franchise’s fundraiser with UNICEF to reach its donation goal of US$1 million within two days. This puts the initiative way ahead of schedule, as the campaign was supposed to last 22 days.

A donation of 580kg of rice to Korea’s Institute for Health and Welfare’s Child Support Agency was also made by the Korean ARMY to commemorate a BTS album release and concert. The Malaysian ARMY hosted an exhibition in 2018 and donated proceeds to the National Council for the Blind, Mercy Malaysia and the Turtle Conservation Society of Malaysia. Thai fans also marked the band’s fifth debut anniversary with a blood drive, collecting 204.1 litres to help 1,500 individuals. The list goes on.

Once again, charity is not the exclusive domain of the ARMY. Before the Bangtan Boys landed, philanthropy was already a thing in K-pop fandom. A big thing.

B.A.P’s fans helped build a school in Ghana. The birthday of EXO’s vocalist Xiumin last year was marked with US$21,600 fan donation to help visually impaired children. Supporters of actor Lee Min Ho also raised US$50,000 for clean water supply in Africa.

Their intentions can be murky, though. Hemmeke laid out in her article that some of these generosity stems from rivalry for their idols’ attention.

However, regardless of intention, these donations do benefit those in need.

Such duality is emblematic of the K-pop fandom. Their superpower – coordination – can be both a force for good and a conduit for toxicity.

The ARMY, for example, organises themselves into pockets of support groups for each other, from studying together online to sharing exercise and cooking guides. “We really don’t just sit around and be fangirls. We help each other,” says Atiqah.

But organisation has a darker side – coordinated attacks on other artists and fan clubs. K-pop fandoms tend not to play well with each other. Due to their size, they can generate an intimidating torrent of hate messages on other groups or individuals.

The ARMY were accused in several alleged transgressions, including attacking the rapper Wale on Twitter for his collaboration with BTS’ RM, sending death threats to indie rapper CupcakKe for her sexually-suggestive tweets about BTS’ Jungkook, and hacking EXO’s official fan twitter account. However, many members of the ARMY maintain that these misdemeanors are committed by a minority of bad apples, or ‘anti-fans’ (individuals out to sabotage a particular group).

Toxicity within the ARMY also seemed to have driven many out of the fandom. Former fans reported that the level of policing means life in the ARMY is not just about sunshine and self-love, but also about scrutiny.

Do you wonder how to classify different types of malicious Twitter accounts? ?

Here are some helpful guidelines. We use these to decide whether or not to block an account ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/xoGtD2lNXr

— Report ARMY (@report_army) February 23, 2019

While there are no hard and fast rules to becoming an ARMY, there are strict – if a little fuzzy – conditions on how to be a ‘proper’ one. For example, singling out one member of BTS to ra-ra over (known as ‘solo-stan’) is generally frowned upon – you have to support the whole band as one, although you are allowed to have a favourite (‘bias’).

Atiqah concedes that the ARMY has its combative side. “We fight with each other, and we fight with everyone else,” she says, laughing.

But she chooses to see the positive aspect of the fandom. It has helped her forged friendships despite her social anxiety and cheered her up through tough times. And she sees the ARMY trying to stamp out the fires in its belly. For example, members are encouraged to ignore ‘anti-fans’ and back counterargument with facts.

“It’s difficult to refrain from shooting back sometimes,” says Atiqah. “We love BTS, and we want to give them the world.”

If the ARMY keeps it up, they just might.

Also published on Medium.

writes about pop culture with the suspicion that it is actually writing her.