Some things never leave you. A secret. A sister. A shattered childhood.

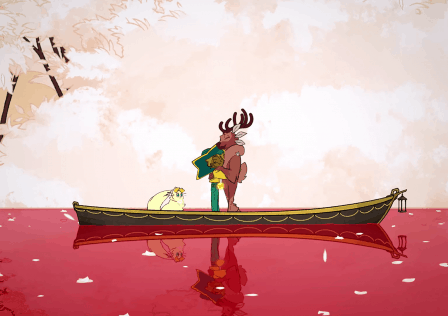

These conjure the goosebumps when watching Two Sisters. The Malaysian indie feature roots its fear factor in psychology rather than cheap jump scares, thus levitating above the corny plane of existence that many local scare films insist on haunting.

Best known for his award-winning film The Beautiful Washing Machine, director James Lee takes time – though some would say too much time – to develop the character and relationship of the titular siblings before things go bump in the night.

The nuanced interaction between them would anchor a film that has little room for spectacles. Shot on a meagre budget of MYR260,000 (US$62,862), Two Sisters fulfills what its indie production company, Kuman Pictures, set out to do – low-budget horror and thriller flicks.

Mei Xi (Emily Lim) and Mei Yue (Lim Mei-Fen) are the two sisters in question. One is a successful novelist, the other a mentally-unstable patient just released from a psychiatric hospital. The siblings reunite and are compelled to return to their abandoned family home. And they lived happily ever after.

Nah. Creepiness ensues, duh. The spooky sightings stab at the already-fractured sisterly bond, but what truly pulls them apart is a mystery from their past, encaged within a locked room in the house.

The movie’s well-composed shots and scores make up for the plodding first act and breadcrumb trails that went nowhere. Its scares may be a tad cheesy for horror connoisseurs pampered with the atmospheric dread deployed by standouts like last year’s The Haunting of Hill House or 2013’s The Conjuring, but ghosts are not the main scare of the film. The real chill comes from the humans.

SPOILERS LURKING AHEAD

Sisters make fascinating pairs in horror movies. More than other sibling pair-ups, sisters are often thought to be rivals. But they are also each other’s keepers and defenders, and often share secrets. The typical portrayal consists of a dominant figure (usually older) and a meeker one (usually younger).

The dynamic lends one the power to put another in her place, even dealing verbal or physical damage. But the dominant sister can also dish out love, attention and protectiveness, which the submissive sibling usually craves.

When bullying and affection are delivered so arbitrarily, a silent unease hovers in the air for the domineered sibling. It’s like having a cosy blanket in the cold and never knowing when it will be yanked away.

This is not to say that all sisters behave as such. It’s a stereotype, one that pop culture also perpetuates. But having grown up with an older sister, I remember treading carefully around her — the coolest person in my entire seven-year-old world. The girl who knew me since birth also knew exactly what to say to make my day crumble. In retaliation, I would tell our parents on her.

Yet, we count on each other for support. Having outgrown my tattletale tendencies, I became my sister’s confidant (and clown). And when I wanted to pursue journalism, to my parents’ abject disapproval, she was the one who went before them and pleaded my case. We are each other’s biggest cheerleaders and biggest pain in the rear. We pulled through together in our darkest days, sometimes simultaneously tempted to wring each other’s neck.

Psychologist Terri Apter explains the bond that both assures and distresses: “The feeling is primitive and terrifying, but I now understand that this is what we learn with our siblings: the terror of being displaced, the confusion of loving and hating the same person, and the necessity of living in a world with other people who are like us and with whom we have to compete and share even those things on which our life depends.”

Such conflicting forces make potent nightmare fuel in a horror story. The tension between Mei Xi and Mei Yue in Two Sisters is subtle, yet more foreboding than any vengeful spirits in the movie.

Xi, the self-assured older sister, seems to care for the timid Yue and promises to never leave her when they were kids. But when Yue grapples with mental illness as an adult and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for years, Xi hardly visits.

Upon reuniting, they returned to their abandoned family home for a short stay. Xi toggles between being warm and cold towards Yue, treating the younger sister like she treats the men in her life – at the mercy of her whims and temper. She decides when to sooth or scold Yue, when to hook up with her lovers, and when to end an affair.

Things come to a head when the sisters hire a locksmith to open the mysterious locked room in the house. The nondescript space held nothing of note besides a picture of their late mother, who had committed suicide. But the opened room seems to unleash secrets that, for reasons that will later be revealed, haunt Xi the most.

From then on, Xi’s grip – on her sister and on reality – starts to slip. Yue began to assert herself; her soft demeanor turns more certain and her loose clothing becomes more formal. Xi, perturbed by her younger sister’s change, descends further into paranoia when hounded by a malevolence that seems tied to her past.

The tables have turned. Xi is now fidgety and gaunt, while Yue is the protector to wake her from terror. Eerily, both sisters began to – figuratively – wear each other’s skin as their distinction muddles. Yet the power imbalance remains, now tipping towards Yue, sowing anxiety within Xi.

Later on, it is revealed that their parents had exacerbated the sisters’ discord. When they were alive, the mother and father’s selective treatment (or mistreatment) on the girls made them unequals. One suffered while the other was spared. That is the real chill-in-the-spine for me – being picked, without discernible rhyme or reason, for abuse by those who are supposed to protect us.

Worse, the effects of her parents’ actions are now, like the house, something that Xi inherits whether she wants it or not. At the risk of giving too much away, the twist showed that Xi’s sense of control is merely a power fantasy – in reality, she is bound, literally and figuratively.

Some may find the ending frustrating. The terror is never vanquished. The protagonist remains trapped. But, seen from another perspective, this is what many childhood traumas look like in reality. It haunts the wounded, sometimes for life. And the horror is that no one else can see it.

Also published on Medium.

writes about pop culture with the suspicion that it is actually writing her.