Here’s a bold claim: Stephen Chow’s Kung Fu Hustle is one of the greatest martial arts movies ever made.

It’s also an important film, parked comfortably among the pantheon of significant wuxia and chopsocky movies like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Fist of Fury, though some may huff at how it seems so out of place, what with its adherence to cartoon logic and utter silliness. That’s like lumping Mel Brook’s Spaceballs with Star Wars and Alien and then slapping on the Criterion Collection of Essential Sci-Fi label. Somewhere, some veins must be popping..

Except Spaceballs is – in my honest opinion, at least – significant. Like Brook’s Blazing Saddles, Spaceballs is a parody of space-fantasy films that comes naturally in a genre’s life-cycle. There comes a point, after making something, that you make fun of it. And to make fun of it well, you need to start taking things apart.

Kung Fu Hustle fills a similar role, and feels like the right movie at the right time. Released in 2004, the movie came a few years within Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger and Zhang Yi Mou’s Hero and The House of Flying Daggers: wuxia films that are more deconstructive and contemplative, and greyer in its depiction of heroism. Kung Fu Hustle’s sillier, subversive core seems suited as the farcical parody that marks the evolution of the genre, like Blazing Saddles to Westerns, or Spaceballs to sci-fi and science-fantasy.

Unlike Spaceballs, though, Kung Fu Hustle doesn’t entirely work as a critical barbeque of the wuxia genre. It’s not to say that it doesn’t partake in its own hearty, healthy deconstructions; but Chow – the venerable godfather of Hong Kong comedy – isn’t just here to merely make us laugh at it. He’s here to make us fall in love with kung fu movies again.

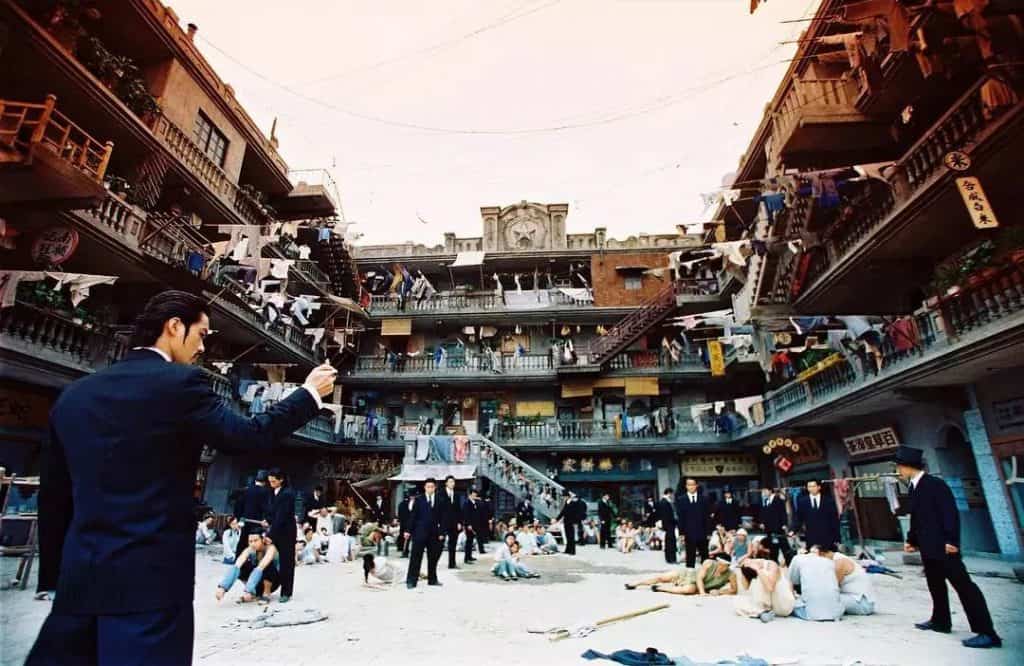

Here’s the gist of Kung Fu Hustle, for the uninitiated. It is Shanghai in the 1920s, a time of well-dressed gangsters that reign over the city with wanton violence and sweet dance moves. Only the poorest are spared from their oppression, with one such area being Pig Sty Alley, an apartment block populated by eccentric, colourful characters living out quiet, peaceful lives; their sole problem being the tyranny of their chain-smoking landlady and her henpecked (or, should I say, hen-eviscerated) husband.

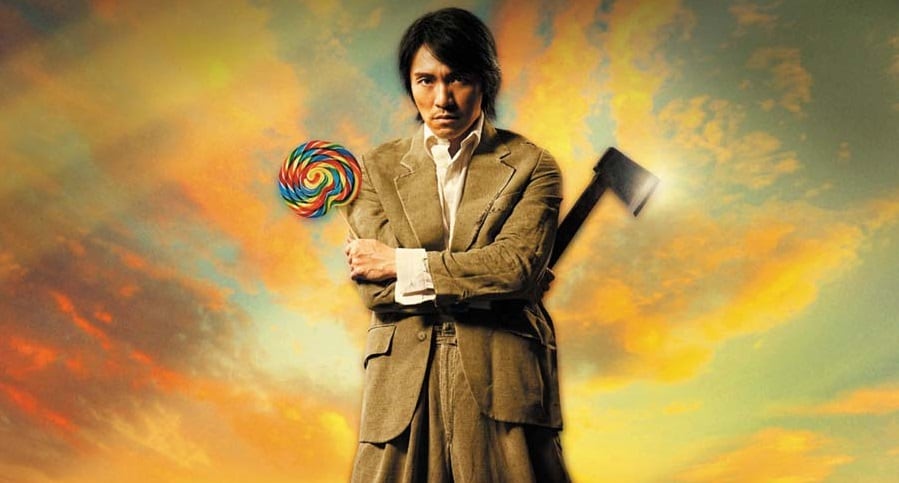

This equilibrium is tipped with the arrival of Sing (Stephen Chow), a counterfeit gang member looking for some easy blackmail target. His sheer incompetence inevitably draws in the notorious Axe Gang into Pig Sty Alley. As it turns out, the crummy apartment block houses some pretty awesome martial arts masters, escalating things into a war. Sing, caught in the middle of the conflict, is thrown into his own whirlpool of self-discovery.

It’s hard to accurately describe Kung Fu Hustle, which is why I’ll let Roger Ebert do it. In his review, the critic extraordinaire calls it “Jackie Chan and Buster Keaton meet Quentin Tarantino and Bugs Bunny” – a most apt description, considering that the movie is a ballet of Corey Yuen-choreographed fights, pratfalls, butt cracks and a scene straight out of the Looney Tunes.

Fitting Tarantino into all these is tougher. For the most part, I believe Ebert is referring to the movie’s cinematic playfulness. Chow has an eye for cinematic flair and careful compositions. If he’s not framing his movie for maximum visual appeal, it’s to reference classic films. Like the best comedy filmmakers, Chow understands that the camera, too, can be a tool for hilarity – if not to keep the audience invested even when the jokes aren’t landing.

Of late, I am starting to see that, like Tarantino, Chow has made a movie amalgamating the things he loves.

Kung Fu Hustle is a cocktail of the Chow’s passion for martial arts and classic Hong Kong cinema. The clues are everywhere, from how Pig Style Alley is basically a pastiche of 1973’s The House of 72 Tenants to the use of classical Chinese opera music, including the ever-effervescent Dagger Society Suite.

And, like a Tarantino flick, Kung Fu Hustle is filmed through a critical and deconstructive lens. It asks a question few Chinese martial arts movies dare to tackle: what happens when martial artists become irrelevant?

This is where the film’s setting comes to play. During the 1920s and 1930, Shanghai was known as “The Paris of the East, the New York of the West” – a period marked by the melting of Eastern and Western culture in a pot of uncertain political and economic upheaval. The heroes then weren’t justice-upholding Kung Fu paragons, but of morally grey, stylish and internally-tormented gangsters – popularised, of course, by The Bund, essentially The Godfather of the East.

So what has become of martial artists during these period? In Kung Fu Hustle, they eke out on mediocre, pathetic lives. The martial arts masters of Pig Sty Alley are a coolie, a Chinese doughnut maker and a tailor, struggling to pay rent and living at the mercy of their landlords – who, as it turns out, are kung fu legends themselves.

The casting of retired, veteran wuxia actors in the roles of the landlords (Yuen Wah and Yuen Qiu) as well as the film’s ultimately villain, The Beast (Bruce Leung), is genius in this respect. It’s not just because the movie homages their involvement, but also serves as a metanarrative of their past glory as martial arts heroes (and villains).

Kung Fu Hustle posits that there is no glory in being the wuxia heroes of old. Time marches on, and the best you can do is to use your mastery of the Tán Tuǐ Twelve Kicks technique to earn a modest living.

Then there’s Chow’s character, Sing, who spends the entirety of the film rejecting the traditional idea of wuxia heroes. For good reason, too – in a flashback, Sing revealed that, as a child, a beggar told him that he was a martial arts prodigy that needs to carry the burden as a protector of justice. Sing spent his hard-earned savings (meant for law school or medical school) in order to buy the beggar’s Buddhist Palm manual and trained to be a martial artist. It doesn’t work – his attempt at saving a mute girl from bullies ended up in misery and humiliation. Disillusioned, Sing vows to become a gangster for a quicker route to get money, women and respect.

After tearing it down, after making fun of it, after telling us that classic heroes have no place in modern times, the film suggests that new generations of heroes and heroism can be born.

Sing’s character arc, which is about rediscovering his inherent goodness and innocence (symbolised, unsubtly, with the lollipop the mute girl kept for him), is also about accepting his role as a wuxia hero. He’s essentially the protagonist in the wrong movie – believing, for the most part, that he’s the rags-to-suits hero of a Shanghai gangster flick. It’s not until the end where he fully embraces his destiny as a martial arts master that he could lay the smackdown on the baddies. Sing’s ultimate move is the Buddha’s Palm, and his mastery of it at the end of the film signifies a sort of enlightenment. Even his behaviour was Buddha-like, offering to teach the villain his Kung Fu rather than punish him.

The fights in Kung Fu Hustle are statements in itself. We have our martial arts movie preferences – some may find delight at the sight of Crouching Tiger’s balletic, elegant sword fights; while some pine for the fast-paced, reality-ground fisticuffs of Ip Man. Kung Fu Hustle’s is a curious mix – a concoction of choreography and wire-fu stirred with large helpings of CGI. It’s like The Matrix, except Chow uses it as a vehicle to showcase a brand of kung fu that is long forgotten – the type that comes with names like the Fut Gar Buddhist Palm technique or the Kwan Lun School Toad Style. These are named techniques that appear in the Jin Yong novels, as well as in the 1964 film Buddha’s Palm – legendary for its rudimentary special effect – brought gloriously back to life.

These were sillier times for martial arts depictions, but they were also an imaginative time – proper superpowers for what’s essentially superheroes. For a period in my childhood, my flights of fancy didn’t involve super strength and laser eyes – it’s about mastering the Eighteen Dragon Subduing Palms to lay waste on evildoers.

Kung Fu Hustle is a return to that. In the guise of a comedy, it could embrace the silly and exaggerated and get away with it, but in the process it showed what used to capture the hearts and imagination of generations. Unassuming and pathetic they may initially appear, the martial artists in the movies are able to flourish wondrously again, as though set free from their shackles. And our veteran actors, as veteran heroes and villains, discover that they have a few more bouts left in them.

The film concludes with the beggar approaching another kid, showing him the manuals of several more legendary martial arts. After tearing it down, after making fun of it, after telling us that classic heroes have no place in modern times, the film suggests that new generations of heroes and heroism can be born.

And that kung fu movies can be great again.

Also published on Medium.

makes it a life goal to annoy everyone with random Disney trivia. When he’s not staring at a screen or holding a controller of some sort, he is thinking about curry noodles. Like right now.