You really cannot blame the critics for panning the Peter Jackson-produced blockbuster disaster, Mortal Engines. Released during the exceedingly competitive December 2018 holiday season, the film had to fight for a share of the profit pie with the likes of Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse, Aquaman and Bumblebee. All three films received strong reviews, whereas Mortal Engines was dismissed as derivative, uninspired and truly crummy.

Based on the novel series of the same name, Mortal Engines is the brainchild of British writer, Philip Reeve. It was adapted for the screen by a trio of writers: Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyen (two long-time Jackson collaborators on his LOTR and Hobbit trilogies).

The fantasy adventure is set in a post-apocalyptic world that is divided into two realms. One is the mobile city of London—powered by a retrofuturistic, steampunk-inspired snarling engine— that “hunts” and absorbs smaller settlements for resources. The other is the stationary region of Shan Guo—a euphemism for Asia—which is made up of an alliance of people of diverse backgrounds, languages and ethnicities, living in harmony with nature.

To make its story less overtly political and more identifiable to its young adult audiences, Mortal Engines weaves into the plot a requisite female protagonist, Hester Shaw (Hera Hilmer) who is hell-bent on avenging the death of her mother. The villain is, naturally, the killer of Hester’s mother, Thaddeus Valentine (Hugo Weaving), who also happens to desire world domination. Of course, no profit-raking blockbuster is ever quite complete without its ubiquitous heterosexist subplot, which is nicely supplied by Tom Natsworthy (Robert Sheehan), a dapper Londoner swept up along Hester’s revenge trip.

Formulaic much? Quite.

Yet, if we can muster the mettle to slog through the hackneyed bits (and there are a lot of such bits!), Mortal Engines does deliver its fair share of clever and novel ideas.

Full steam ahead into spoiler territory!

Mortal Engines upends the capitalist model of development by portraying London as an ever-advancing empire that gobbles up smaller cities in its wake yet, ultimately, fails through its own hubris. Successful Shan Guo, on the other hand, is quite happy to eke a modest and sustainable communal living without riding roughshod over any other region or harming the environment.

The wheels of progress are metaphors made flesh (or more precisely, steel) in the film, for the city of London sits atop gigantic tank treads that never stop turning. To feed its hubris, this hulk of an engine requires raw materials, which the industrial machine of the London Empire tracks from afar, assessing potential victims for their worth as fuel and labour resources.

Once deemed worthy, these smaller mobile cities are then advanced upon. London literally gobbles them up, leaving miles upon miles of muddy tracks in its gnarly wake. Thaddeus Valentine, the big bad of the movie who happens to be a historian, calls this form of evolutionary consumption “Municipal Darwinism”, a sly nod to the Englishman who indirectly helped shape the racist ideology of the Western world in the last two centuries.

Now isn’t that just a genius allusion to the machinations of 19th century British industrial revolution? And to think quite a number of film reviewers called Mortal Engines a Mad Max clone. Just because monstrously massive moving machines are mowing down a post-apocalyptic world to the beat of a JunkieXL soundtrack does not mean the film is trying to channel George Miller’s masterpiece.

To my mind, Mortal Engines is a very thinly veiled allegory of Victorian Britain, an era often seen as the zenith of the British Empire. This is the period that birthed steampunk—that much loved genre of science-fiction I usually loathe.

The Victorian era that steampunk draws upon for inspiration is the period where a fifth of the earth’s surface was under British dominion.

My beef with steampunk is because it tends to depict the steam tech revolution with a benign nostalgic sheen: quaint technology with lots of interlocking gears and knobs, tinker-worthy gadgetry, man’s first earnest forays into cyborg tech, tons of top hats, oodles of goggles, and women decked out in corsets, lace and frilly hems.

Not many want to depict the atrocious working conditions that greatly shortened many a working class lifespan during the height of the industrial revolution, the forced child labourers, the insane amount of pollution (the London fog is actually smog from factories), the rapid and unsustainable depletion of the earth’s resources, and the repressive sexual climate—so brilliantly dissected in Michel Foucault’s seminal book, The History of Sexuality.

Mortal Engines, in contrast, stripped the steampunk era of its romanticism — and its excess of top hats and corsets, thankfully.

It reminds people that the great British Empire would not have even existed were it not for its many colonies all over the globe. The Victorian era that steampunk draws upon for inspiration is the period where a fifth of the earth’s surface was under British dominion. Queen Victoria’s subjects made up 25% of the world’s populace. Colonies decimated their natural environments to embark on mining and monoculture farming designed to feed the engines of the industrial revolution in London.

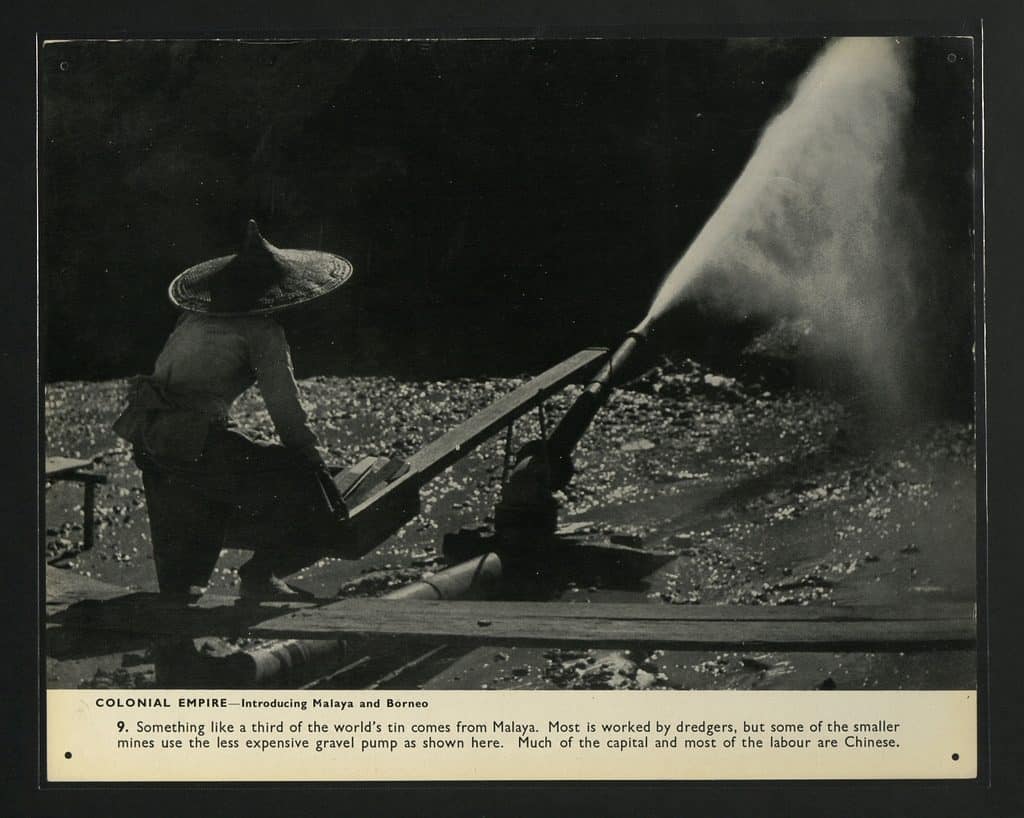

My own country, Malaysia, was an integral cog in the wheel of British advancement and progress into the 20th century, funnelling tin ore and rubber to an empire that needed both but had none.

According to John Drabble, a honorary research associate at the University of Sydney and the author of classic texts on Malayan economic history, rubber and tin were Malaya’s main exports to Britain because they were instrumental in the manufacture of canned food and tyres for the booming automobile industry.

Rubber plantations replaced food crops like rice, the staple food of the nation. Ironically, in return for selling rubber at cheap prices to the British, we got to buy imported canned food in cans made with our very own tin! What a nice way to close the colonial loop.

Thanks to the British, thousands of Chinese and Indian migrant labourers were shipped to work the tin mines and rubber plantations. This influx of immigrants disrupted existing social structures, caused social unrest, and led to the British political strategy of divide and rule, which was not only racist but also fomented the racialised political system that exists to this day and has had lasting negative impact on Malaysia and its populace.

So it is unsurprising that my favourite scene in Mortal Engines occurs at the very end, when the British march of progress eventually grinds to a distinct halt, right at the doorstep of Shan Guo. Then, the defeated—and largely white—Londoners had to eat humble pie and seek refuge among the Shan Guonese. Their engine of destruction and domination is well and truly dead; their empire will now be subsumed into the rest of the world and the Londoners will need to adjust to a new world order peopled by those once labelled as “Other”.

Talk about a satisfying resolution to a film! I cannot count the number of times I have thoroughly enjoyed 75% of a film, only to baulk at a subpar ending or a ridiculous denouement. For Mortal Engines, it was decidedly the opposite: suffer the tedium of the first 90 minutes then wait for the upending. It’s the least you could do for the British empire.

C Nge makes it her mission to write about films that have the power to change the world: one heart, one mind at a time.