This year has been a year of in-betweens. As the Covid-19 pandemic torpedoes around the globe, and people hunkered down indoors to avoid the highly infectious virus, life took on a strange sense of duality.

Those of us lucky enough to stay alive were caught between the tragic news of lives loss and the shelter of home. Those of us lucky enough to keep our jobs were caught between gratefulness and the pandemonium of home life (feat. children going mad being stuck indoors). Those of us lucky enough to enjoy our time at home were caught between the peace of not having an obligation to attend social events and the anxiety of seeing the economy in freefall. Those of us who are lucky enough to feel lucky were caught between not wanting to die and wanting to throw a party.

It was apt, then, for Spiritfarer to be released during this time. The game is loosely inspired by the poster boy of in-between-ness – Charon, the folkloric ferryman. In Greek mythology, Charon ferries souls of the deceased across the Rivers Styx and Acheron to reach the underworld, and receives a coin (obol) in return.

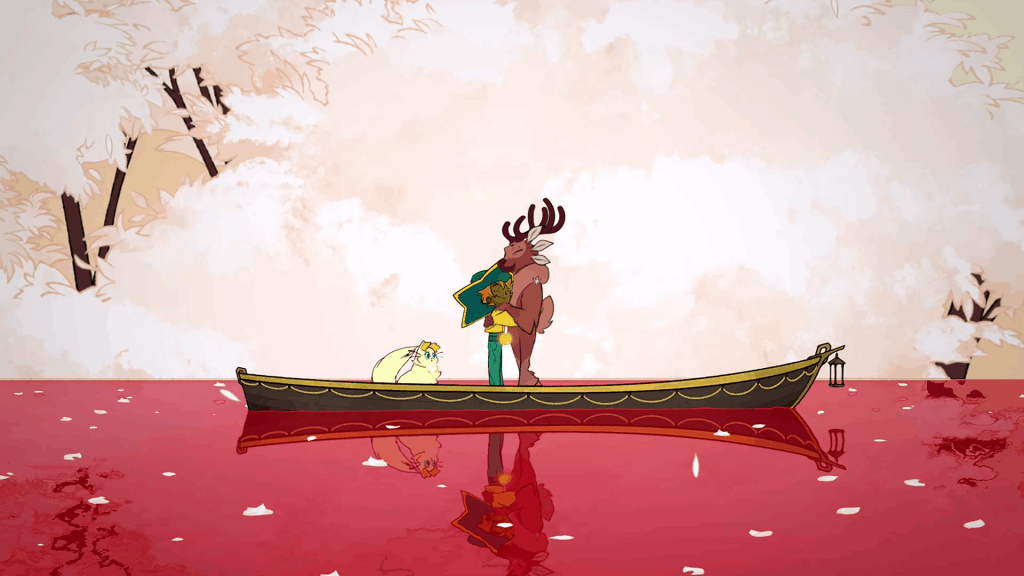

In Spiritfarer, Charon is replaced by the cheery Stella and her fluffy cat, Daffodil. Together, you manage a ship and bring spirits aboard to the underworld. The game is playable in both single or local co-operative mode – Player One controls Stella, and another can join in as Daffodil.

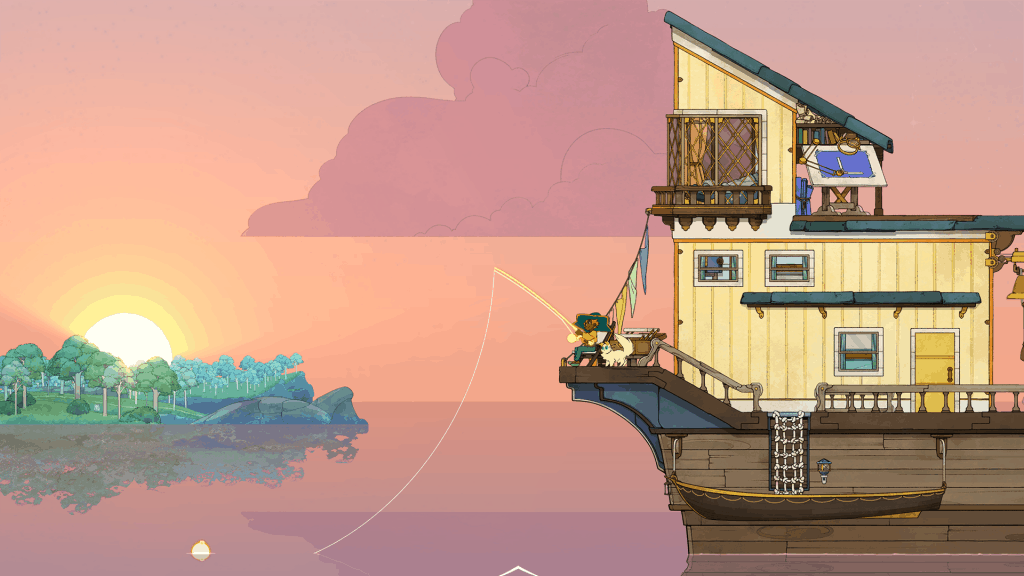

With its vibrant yet harmonious visuals, a soothing soundtrack, a big map to explore, dopamine-pumping mini games, conversations ranging from affectionate to zany, and a cat that actually does chores – Spiritfarer is everything I want (not just in a game).

But a finessed execution is not the only thing that makes Spiritfarer a unique experience. Developer Thunder Lotus, known for monster-laden hits like Jotun and Sundered, called Spiritfarer “a cosy management game about dying”. That is no small statement, and a highly evocative one for this management game fiend. I dived in fully-prepared to pay some emotional cost for a spin on my favourite genre.

What I was not prepared for, however, was my inordinate investment into the characters that gives the inevitable heartbreak that extra twinge. Simultaneously, every moment in the expansive and gorgeous world buoyed me with bliss. Like death, the game straddles the narrow path between relief and grief.

Much of the game is about running a sort of bed-and-breakfast on water – a departure from the journeys of the mythical Charon on his dinghy. Stella and Daffodil (yes, kitteh is an equal partner) wake the passengers up in the morning, cook for them, grow the ingredients needed for their meals, craft materials to build and decorate their rooms, run errands for them, and dish out hugs when they need it.

The ship would be upgradable to whale-like proportions. Stella and Daffodil roam the map and stop at various islands for resources, mystery boxes and plot progression. The passengers (literal spirit animals) in their care are the ones who decide when they are ready to move on to the Everdoor – a portal to the underworld inspired by an actual bridge in Germany, called the Rakotzbrücke, which creates a circle in its reflection.

Spiritfarer is touted as ‘death-positive’, which is a movement to encourage open discussion about the often-taboo topic: death.

Death in games is no novelty – kill or be killed is pretty much the point of many titles out there. But it is refreshing how Spiritfarer approaches the topic — with compassion. It is a game about providing care to those at the last moments of their existence, no matter if they are thankful or testy, culminating in a game that warms and dims the soul in equal parts.

During the nautical travel, each character’s backstory unravels through their conversations with Stella. There are no moralistic lessons to these tales, no cautionary fables. These are stories of being alive told by the dead, who can be big-hearted and good-natured as they can be rude and petty.

“One of the very first intentions we had was not to impose a message on people. We didn’t really want to say something specific except that we wanted to get accustomed to talking about death more. It’s a haunting subject, it’s both extremely common and extremely dramatic,” Spiritfarer’s creative director Nicolas Guérin told PC Gamer.

According to Guérin, the characters were inspired by the development team’s own loved ones. Perhaps that is why each of them came alive in their own way, even the ones whom I initially felt little sympathy for, and my heart shrivelled a little when I cuddled them goodbye at the Everdoor.

This is where the management aspect of Spiritfarer went beyond gameplay to be a coping mechanism. No matter how sad I was at having to send a spirit to their final moments, there was still flour to mill, sheep to shear, and wanton soup to cook. For some, the chores may feel rote after a while, but it allowed me (or rather, Stella and Daffodil) to keep their hands/paws busy while the farewell sank in. Of course, the joy that the other passengers expressed when I made the extra effort to prepare their favourite meals (which required some trial and error to find out) was also healing.

Productivity is no small comfort in a time of loss. It reminded me of attending the long Chinese wakes, where family and friends sat around folding ‘paper currency’ for the deceased while chatting about bygone lives. At the end of the wake, our fingers may be stained with the cheap glitter of the paper and our cheeks stained with tears, but the pain was no longer thrashing in our hearts. It had found a corner to settle in, likely forever, but at least its claws were not drawing blood.

Spiritfarer provides a vessel to navigate the tumultuous time of death. But, to me, Spiritfarer is also a story about being stuck. The passengers on the ship were not waiting to go through the Everdoor; it seemed like they were stalling. All of them had last errands to run or last knots to untangle before they embarked on their final journey, even though it remains a mystery if they were ever truly satisfied.

The spirits would only request Stella and Daffodil to send them to the Everdoor when they were ready, and some took longer than others to get to that point. And sometimes, they did not come un-stuck – suffice to say that Stella and Daffodil did not take every passenger to the Everdoor. As the game unfolds, the player would discover that the star-hat captain and her cat have more in common with their dawdling passengers.

However, befitting of its dualistic nature, a game about being stuck also showed me the value of moving on, and of saying goodbye when the time is right. When I had a sense that the game was coming to an end, I tried to stall like my passengers, running all the errands I could find, maxing out the recipes I could discover, and travelling the map end-to-end just in case I missed out any locations. And the game allowed me to do so. But it soon became tiresome. I was prolonging my play just for the sake of it. The experience was no longer pleasant. It took me a while to realise that I am in limbo – an unending in-game existence even though the game has pretty much run its course.

I was reminded of my 99-year-old grandmother, who now lays largely immobile on her bed after several paralysing strokes, sustained by feeding tubes and round-the-clock care. She cannot speak, or eat, or even turn her head to the right, and she cannot end. It was not that she was unwilling to leave the world, but her heart simply keeps beating. She no longer displays any will to live, but that appears to have no effect on biology. All we could do is to ensure her comfort while suspecting that nothing would comfort her more than a dignified death.

I finally moved on to my finale in Spiritfarer, because sometimes having an ending is a privilege that should not be squandered. There is grief, but there is also relief, and life often happens somewhere in between.

Also published on Medium.

writes about pop culture with the suspicion that it is actually writing her.