Nothing prepared me for the works of American indie filmmaker Kelly Reichardt.

When I fall for the work of a filmmaker, I usually fall firm and fast. I was like that with Wong Kar Wai, my first auteur crush: those first five grainy minutes of Happy Together (1997) gripped me so tight, I spent the next few years studying, discussing, and writing about his films in graduate school.

But with Kelly Reichardt, it was nothing like that, never a crush. It was more like a casual acquaintance that slowly blossomed into a serious friendship, and eventually matured into love. Her films exact a slow burn on my psyche and images from them continue to haunt me.

For instance, I still like to run through a few scenes from her most recent film, Certain Women (2016), in my head even though I watched that film more than a year ago. My favourite scenes from this film about four women with intersecting lives, are those that depict a Native American female rancher (a riveting Lily Gladstone) going about her daily chores of feeding her horses and cleaning out their stable in the middle of winter. I also recall scenes of young lawyer-substitute-teacher Elizabeth Travis (Kristen Stewart) conducting dreadfully dull adult education classes in a small town in Montana. (Full disclosure: I’m a teacher myself so boring classes really fascinate me).

It may seem unusual that these are the scenes I remember from Reichardt’s films, because they are not wrapped up in high drama, suffused with gripping emotional intensity, or dense with memorable dialogue. Truth be told, her films contain few such scenes. It is almost as if she resists falling into such hackneyed attention-seeking traps.

Undeniably, Reichardt makes the kinds of films that is not likely to appeal to audiences weaned on cinema of the spectacle: there are no fast-paced chase scenes, no fancy high-tech special effects, no chart-topping soundtracks, and often very, very little dialogue. Her most visually affecting scenes are those told sans words, with only diegetic sound.

Despite the scarcity of these familiar trappings of popular cinema, Reichardt’s films manage to do something few films these days can claim to do: they draw you in—ever so slowly, ever so sure-footedly, and ever so compellingly.

Lily Gladstone in Certain Women (2016)

In a world suffused with incessant stimuli, Reichardt’s work serves as a curiously meditative balm that borders on the hypnotic, which keeps me coming back. But I am also mindful that much of my preoccupation with her work has to do with her choice of characters and her subject matter: women and women’s lives.

Without a shred of sentimentality, her films document the minutiae of everyday life, and in particular, the lives of women. Reichardt captures a tedium that is increasingly palpable to women the world over because it is our lived reality, even though a great many films pay these realities short shrift. Maybe it is because such realities are deemed boring and inconsequential. Yet seen through the eyes of women, such tasks are far from meaningless; they structure our lives, they shape our moods and appetites, they mess with our psyches and encroach into our relationships.

Meek’s Cutoff (2010)

She frequently chooses to do something few filmmakers today care to: allow a scene to unfold in time, uninterrupted.

Reichardt’s films are like a healing salve for a long, tiring and tiresome day because she is a master at capturing tedium in all its forms and fecundities, and elevating it to the status of art.

In Wendy and Lucy (2008)—a quiet film about a girl and her dog (Lucy, the canine star of the film, is Reichardt’s dog in real life)— it is the endless waiting that engrossed me. I confess I am an incredibly impatient person and I hate waiting for anything, but I never would have thought watching Wendy (Michelle Williams) wait would so transfix me. Wendy waits for the mechanic to open his shop so that she can get her car fixed, she waits for a phone call from the pound to tell her if her lost dog has been found, she waits at the bus stop, she waits at the kerb, she waits in her car, she waits against her car; she bides her time, waiting for good news when only bad news ever seem to come.

Michelle Williams and Lucy the dog in Wendy and Lucy (2008)

But it is this constant waiting that builds Wendy’s resilience, her tenacity and her fortitude. Her patience is its own reward, just as ours makes us more discerning and reflective viewers of films.

In Meek’s Cutoff (2010)—a film very loosely based on the true story of early white settlers moving west to Oregon in 19th century America—the lives of the three women characters revolve around the tedium of setting up and breaking down camp, hauling water, collecting dry bits of woods to start fires to cook food and make coffee, washing dirty dishes and doing laundry. Reichardt devotes so many scenes to such activities that when one of the women, Emily Tetherow (Michelle Williams, again) diverges from the routine, we pay careful attention.

Neal Huff (left) and Paul Dano in Meek’s Cutoff

These are women who eke out a life without making a living. They earn no money but they get by. Their daily domestic drudgery is not a side note to a more compelling plot; it is the plot.

Shot in a cinéma vérité style, Reichardt respects her characters by showing us the full compendium of their daily activities and by so doing, accords their lived experiences the visual levity they deserve. The work of surviving the banality of life is as tough a job as any and can command beauty in its erstwhile simplicity and unaffectedness.

In an interview with The Guardian, Reichardt reveals that her research into the lives of 19th century women on the Oregon Trail through their journals showed her that, “When you read these accounts you see just how much the traditional male viewpoint diminishes our sense of history. I wanted to give a different view of the west from the usual series of masculine encounters and battles of strength.”

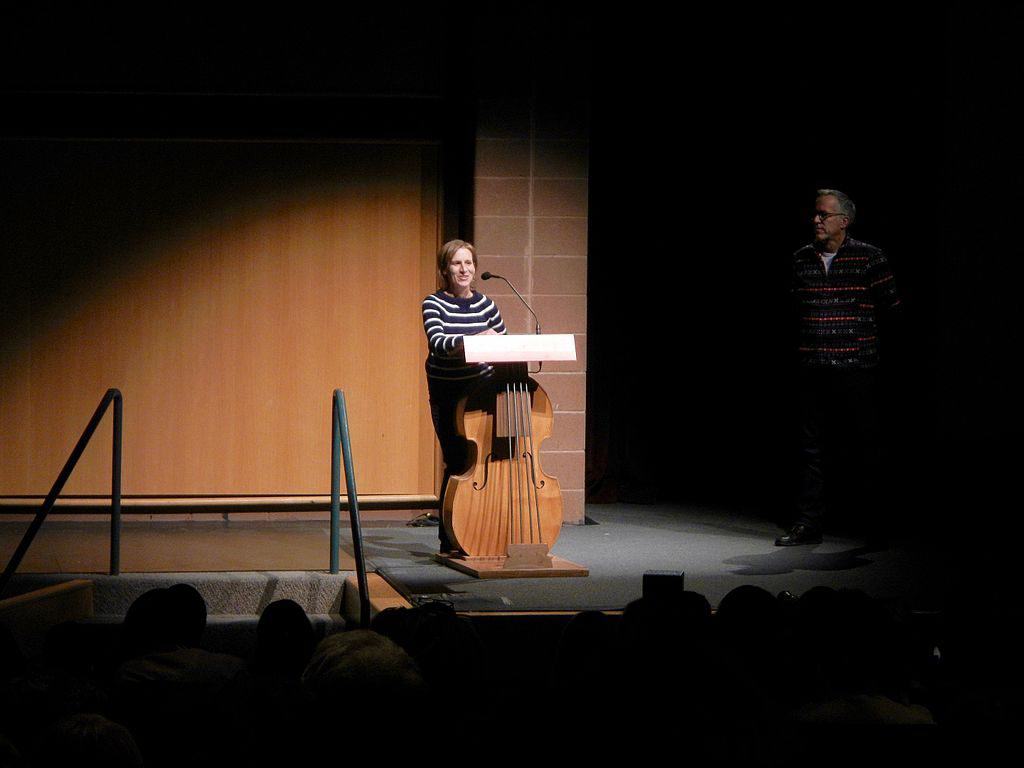

Kelly Reichardt (centre) at the 2016 Sundance while the film festival’s director John Cooper looked on

The Western film genre is replete with such masculine views of the world so it makes sense that Reichardt would make a film that deconstructs and redefines the genre. Her focus on the stalwart women settlers enables us to relook the defining features of Westerns through feminist lens. She achieves this focus not only through characterisation and storytelling but also through cinematic techniques.

With her impeccable framing and masterfully constructed mise en scène, she frequently chooses to do something few filmmakers today care to: allow a scene to unfold in time, uninterrupted. She does not rely on fast and frequent cuts to piece together a story; rather, she builds a narrative using the feat of endless patience. To be sure, there is no rushing Kelly Reichardt. And if, by the dint of your own fortitude, you are able to quell your restlessness, the cinematic rewards are immeasurable.

Reichardt’s works remind me a great deal of Iranian New Wave cinema, where a minimalist visual style meets brazenly straightforward stories about seemingly trifling events. The camera patiently, quietly and unobtrusively documents. There is realism in repetition: watch an actor do the same thing three, four, five times and the tedium elevates the acting to the realm of the lived. Actors no longer act, they do, and in their doing, they become aware of how their bodies inhabit a space and live in it.

More than just plot and characters, there is poetry and lyricism in this kind of cinema; it is no surprise that Reichardt has been called the cinematic poet laureate of America. In addition to her unique visual choices, Reichardt films are important because they enlarge the space for and diversify the contributions of women filmmakers.

Despite recent shifts in the Hollywood film industry, largely due to the #metoo movement, there is no denying the still limited space and opportunities afforded to women filmmakers due to a combination of financial impediments and creative differences. This holds even truer for indie women filmmakers like Kelly Reichardt, who eschews the blockbuster expectations inherent in the top down, profit-driven studio system, to strike out on her own.

Meek’s Cutoff

Reichardt’s ability to make films on her own terms and to tell stories the way she wishes to tell them is hard won, but she understands that financial freedom is an essential facilitator of creative freedom. She teaches at Bard College to make ends meet and to diversify her ideas and influences. Every two to three years, she makes small films on modest budgets and has been doing so since 2006.

A great many films today are made to feed not the engine of creativity but the engine of capitalism, which runs on the fuel of adrenalin and spectacle. Action and drama are densely packed into each frame, and every second has to reverberate with a memorable score overlaid with cool visuals, impressive SFX, and celebrity eye candy.

A filmmaker who resists recycling these elements in her film is a filmmaker who is immune to the thrall of Hollywood and the studio system. Kelly Reichardt is such a filmmaker, and her distinctive vision and uncommon aesthetics need no Oscars.

C Nge makes it her mission to write about films that have the power to change the world: one heart, one mind at a time.