Seven years is a long time to germinate a film but some movies are worth the wait. Just shy of 90 minutes, Guang is a visually evocative tour de force worthy of the awards it received even before it hit Malaysian cinemas last month.

Guang began as a 14-minute short film about an autistic boy and his brother, which won the hearts of the judges at the 2011 BMW Shorties competition and its grand prize. The short, written and directed by Quek Shio Chuan, was inspired by and dedicated to his real life autistic elder brother, Shio Gai. It would later go on to win numerous awards worldwide and start Quek on a mission to expand his short into a feature-length film.

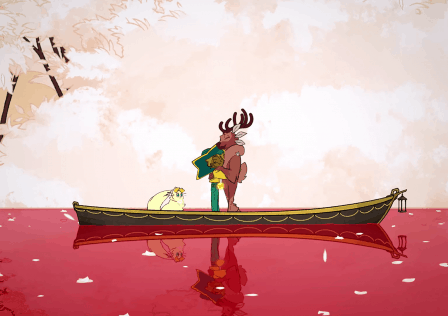

Guang is a powerfully affecting film about brotherly love, sacrifice and filial piety, regret and redemption—themes relatable to every Asian viewer—but at its heart, Guang is a story about quests.

Spoilers ahead

The primary quest that drives the narrative is the one undertaken by protagonist Wen Guang (Kyo Chen), an autistic man living with (and depending on) his increasingly-frustrated younger brother (Ernest Chong). The film follows Wen Guang on a mission to locate essential parts with which to assemble a one-of-a-kind musical instrument. Think an archetypal hero’s journey à la Joseph Campbell; it involves obstacles along the way, as well as new friends and unlikely allies, and ends with a fitting reward and a neat resolution.

But Guang is a story not of one quest, but two. The second quest involves the co-protagonist in the story: Wen Guang’s nameless younger brother, who the former calls “Didi” (the Mandarin word for younger brother) throughout the film. When Wen Guang goes missing in the second act, Didi embarks on a quest to find him.

In order to find his brother, Didi has to retrace each and every step his brother took in the few days leading up to his disappearance. Didi talks to the same people Wen Guang talked to and walk the same streets that he walked, all in an effort to approximate an understanding of his brother. To figure Wen Guang out, Didi literally had to walk a mile in his shoes. Thanks to his quest, Didi realised he spent so much time taking care of his brother’s financial needs that he neglected to pay attention to his imaginative ones.

While the excitement of Guang is fuelled by the narrative propulsion of the quest structure, the dramatic intensity of the film revolves around the creative genius of its autistic protagonist, beautifully developed through the film’s resonant and affective score. The familiar saying, “Music is a window to the soul” is taken very seriously in the film because it is only through music that we feel for Wen Guang and feel as him.

Being autistic, Wen Guang does not say very much and his facial expressions reveal very little, but his love for sounds is evident from the opening scene of the film. The director’s brilliant conceit is to use the film’s score to communicate what is going on in Wen Guang’s mind. The score charts his shifting moods and fluctuating excitement levels; it tells us when he is filled with gleeful delight, even when external circumstances may seem particularly daunting.

Director Quek’s younger sister, Shio Yee, wrote and sang the theme song, titled Abstract Painting, which perfectly captures the spirit and tenacity of Wen Guang. The protagonist is as difficult to decipher as an abstract painting but the value of his art lies in his resolute and unwavering sense of self. He may look pitiful when he traipses all over the city, looking lost, unwashed and unkempt, but the music tells us otherwise: this is a man on a mission to rebuild his dreams and he will not be deterred. A line from the song says it best: “You walk your own path, the path of no regrets.”

Very commendably, the film shies away from typical strategies of the pity bandwagon: it does not make Wen Guang the victim of random bullies at school or work (in fact, the only two people who beat and berate him are his mother and brother); it does not portray him as scared and naive (Wen Guang is often quite courageous and willing to go to places on his own that others would not go, i.e. the landfill); and most of all, the film does not make him out to be an innocent autistic boy with a good heart.

Wen Guang has intensely human foibles, ones that are usually associated with normal, non-autistic people. He acts out when he does not get what he wants, he rebels when he is told to do something he dislikes, and he is vengeful and vindictive when Didi destroys his painstakingly collected stash of glassware. Like any normal son made aware of his inadequacies, Wen Guang has complicated feelings for his mother and this is captured with great complexity and nuance in his behaviour at her deathbed.

In essence, the virtue of the film is its refusal to portray Wen Guang as a victim to be protected and pitied. Instead, director Quek uses visuals and music to celebrate what makes his autistic protagonist resilient, tenacious and unique.

I have always believed that a film that dwells predominantly in pity will always come up short. When you pity someone, you feel badly for him or her; you may not really understand them but you feel sorry for their plight. Pity comes from a place of sympathy, not empathy—a place where you may feel sorry, but never truly share the worldview of the person you pity.

For me, for a film to be truly great, it would have to fully immerse me in the mind’s eye of another—no matter living or dead, real or fictive—and to enable me to feel as they feel, think as they think, and imagine as they imagine. It would be the kind of film that opens me up to an array of emotions, including pity, but that also enables me to transcend them and consider other means of apprehending the world within the film.

Guang deftly uses the home surrounding as a visual metaphor. The water runs clear in Didi’s prized aquarium (left) when he and his brother, Wen Guang, are chummy. But as their relationship deteriorates, the aquarium grows murkier.

Guang is a film that unabashedly journeys into the universe of feelings. I watched the film twice and both times I heard audiences chortle and chuckle, gasp and exclaim, buoyed along by the divergent emotions elicited by its simple yet powerful story. Unsurprisingly, we also wept, openly and sometimes uncontrollably. The strange thing is that I not only cried when my heart broke, but I also sobbed when my heart sang, something I very rarely ever do.

I was able to feel such conflicting emotions because the film did not just dwell in feelings, it also willfully carried me to the precipice that is Wen Guang’s strangely beautiful mind, and challenged me to dive into its idiosyncratic abyss.

And I did.

Also published on Medium.

C Nge makes it her mission to write about films that have the power to change the world: one heart, one mind at a time.

2 Comments

talexeh

Dec 29, 2018 9:29 pmNice write-up but I’m interested to understand your take on the scene where Didi came home to a kettle filled with antiseptic ointment. 🙂